The old man and the game of trust

Let us play a game, you and I.

Let us play a game, you and I.

I will give you some money – here, have this. Of course, it’s not a joke. You can take that 100$ bill and walk out of here. No one’ll say a thing. Or come after you.

Or you could do something nice. You see young Joe over there? You don’t know him? Of course you don’t. Doesn’t matter, he’s a good lad. Let me tell you what you can do. You can give him a small share of that 100$ you got. And I’ll say what, however much you decide to give him, I’ll give him twice the amount you do, so that he now has a tight little bundle. And now that he has so much money, I’m sure he’d be feeling grateful, and give you back some of that cash. So, on your part it’s not really a gift, but an investment, one that could make you a nice little packet in the end.

How will you know that he won’t take the money and run, you ask? Well, I can’t answer that. It’s up to the goodness of your heart, and your trust in the goodness of your fellow man. As I said, I won’t make your choice for you. You decide how much you want to give, and he decides how much he wants to give back.

You’ll give him 10$, you say? Fine, fine, I’m sure he’ll appreciate it. By and by, you see this little bottle? Why don’t you take a sniff of that? Nothing that’ll harm you, I promise. All natural, all the goodness of the earth in this little bottle – a perfume of my own invention. And while you smell that and think over how much you want to give young Joe here, let me tell you a little story.

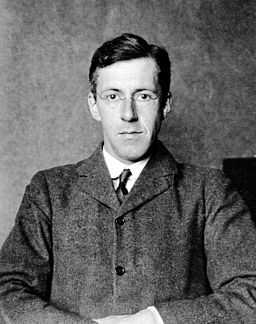

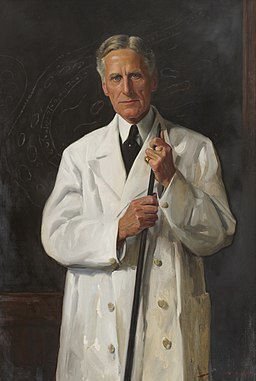

Bell, now, he was a smart man, and quickly did he observe the benefits of the extract in helping deliveries and preserving the health of women post-childbirth. In 1927, a group of scientists at the Parkes Davis research laboratories came up with a name for this little beauty – Oxytocin, from Greek ωκύς, meaning quick, and τοκετός, meaning childbirth. Oxytocin, the active component in Dale’s pituitary extract, quickly made its way into maternity wards worldwide, to assist women whose labours were slow and complicated. In fact, it’s still used there today.

Just what is this oxytocin, you ask? Well, oxytocin is a hormone, a chemical messenger that travels via the blood and gives your organs their marching orders. Oxytocin is dumped into the blood by the pituitary gland I told you about, but that’s not where it’s made. Nope, in fact it’s in the brain that most of your oxytocin is made, in a quaint structure called the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus sends its oxytocin down into the pituitary, and the pituitary decides to release it into the circulation whenever necessary.

What does it do there, you ask? Well that’s what I have been waiting to tell you since the beginning! You see, by the 1980s and 1990s, men (and women too, sure) of science were becoming very curious about what oxytocin does, besides stimulating one’s womb and mammary glands. They already knew that oxytocin levels hit the roof when a woman gives birth, and later when she breastfeeds. Does all that oxytocin floating around affect her brain, affect the way she thinks?

But first let me tell you, no one pithy molecule can be enough to bring about all the changes that arise in a woman’s brain and behavior once she becomes a mother. Her aspect becomes a unique combination of tenderness over the offspring, and aggression towards anyone unwise enough to cross the said offspring. Over the years a bunch of studies have come up that show that oxytocin does something to the brain that makes you love your ugly offspring – it makes fathers act more positively towards their babies, it makes women more responsive to an infant’s cries. It makes innocent rat females, who have never been near a male rat in their lives, go and pick up distressed pups as though they were the ones that given birth to them. It makes monkey fathers give away more food to their offsprings. In other words, it helps you take baby steps towards ideal parenthood.

So you now have oxytocin, a wonder drug for women in labour, and an influencer of baby-love and romantic fidelity. But that’s barely scratching the surface. Oxytocin can help you recognize whether the face opposite you is mad or sad, it can make you gaze deeply into another’s eyes. And as a little experiment published in 2005 showed, it can decide how much you trust a stranger with money. You see fellas, these scientists in Switzerland came up with a game called ‘The Trust Game’, and got a bunch of students to play it. Half of these players were allowed to sniff a little whiff of oxytocin before the game. And guess what the study found? The players who smelled the oxytocin in the beginning, tended to be way more trusting than the rest.

What is the trust game, you ask? Heh, you have a short memory, don’t you?

Anyway, now that you have heard my story, and taken a good sniff outta that bottle, it’s time to answer me, my good man. How much are you really willing to give young Joe out there?

Further reading

- Carson, D. S., Guastella, A. J., Taylor, E. R., Mcgregor, I. S. & Mcgregor, I. S. A brief history of oxytocin and its role in modulating psychostimulant effects. J. Psychopharmacol. 27, 231–247 (2013).

- Veening, J. G., Jong, T. R. De, Waldinger, M. D., Korte, S. M. & Olivier, B. The role of oxytocin in male and female reproductive behavior. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 753, 209–228 (2015).

- Marlin, B. J., Mitre, M., James, A. D., Chao, M. V & Froemke, R. C. Oxytocin enables maternal behaviour by balancing cortical inhibition. (2015). doi:10.1038/nature14402

- Young, L. J. & Wang, Z. The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nat Neurosci 7, 1048–1054 (2004).

- Kosfeld, M., Heinrichs, M., Zak, P. J., Fischbacher, U. & Fehr, E. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. 435, 673–676 (2005).

Featured image credits – An Old Man Putting Dry Rice on the Hearth, 1881, Vincent van Gogh

I love love love this writing style Shreyaa 🙂

🙂

So well written. Loved it. 🙂

Nice article. Loved it.

Out of nowhere, I ended up on this website and I must say, I enjoyed this article a lot.

Thank you 🙂

zv2e30

iiqism

63jq0a